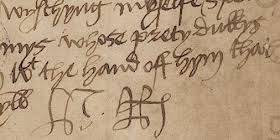

In Henry VIII’s letters to Anne Boleyn I found these lines:

“Mine own Sweetheart………

Wherever I am, I am yours……….

Written by the hand of him who is, and always will be yours….”

The passion found in those lines and the seventeen letters he wrote in the early days of his arduous pursuit of her have evoked sighs through the centuries, regardless of age, gender or culture. Love needs no definition. Its magic needs no explanation. How all that passion between Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn changed the course of English history and placed Anne Boleyn, as Queen of England, on a scaffold to be executed by a French executioner, a swords-man, only a few years later, has been the source of a five-hundred-year-old controversy.

How these very personal letters ended up in Rome, hidden, for centuries, in the Vatican archives will never be known. One can only assume that they were stolen by supporters of Katherine of Aragon, the Queen that Henry VIII sought to divorce despite their Catholic marriage vows. According to Henry, his union with Katherine was sinful and unlawful in the eyes of God, incestuous in fact, due to Katherine’s prior marriage to Henry’s brother Arthur. His grounds for divorce were that this sin had cursed their union resulting in their inability to produce a male heir for the sake of England. Although the Queen swore her brief marriage to Henry’s brother was never consummated and the Pope had granted dispensation for their union, Henry didn’t budge. It was widely known that making Lady Anne Boleyn his wife and Queen had become Henry’s obsession. An obsession that eventually led England away from the grips of Rome and towards a religious reformation with Henry VIII as the Supreme Head of the English Church. Perhaps the Pope himself read these letters meant for Henry’s darling Anne and realized just how obsessed Henry had become. And then quietly had them buried in the archives.

Through my own research, I found that these letters were not available for public viewing at the Vatican, and rarely has more than one letter ever been sent to foreign exhibits. During a recent trip to Rome, I made it my mission to see these letters for myself and determine how they had fared over the centuries. This turned out to be a far more difficult and yet a far more interesting quest than I could have imagined.

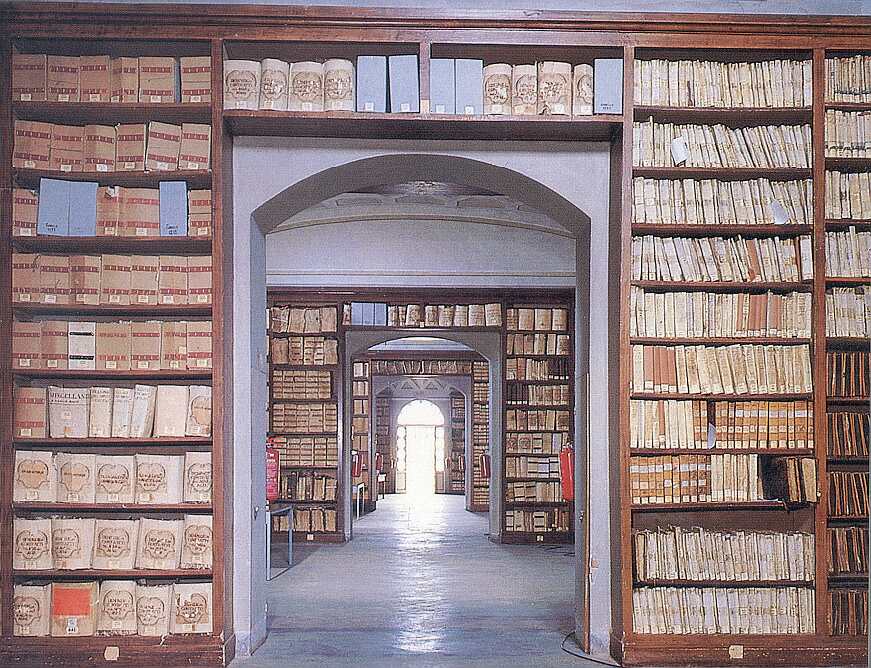

The letters are kept in the archives of the Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana, the Pope’s private library which was founded in 1475. Although originally intended solely for His Holiness, the Pope himself, and a few eminent scholars, since 1883 it has been open to “qualified readers,” by advance approval for those who meet the Vatican’s stringent list of criteria.

In addition to an extensive application, I submitted a letter of introduction and replied to in-depth questioning about why it would not suffice to examine copies of the originals. Many letters passed between the head of the Dipartimento Manoscrititti Vaticana and myself before I was finally granted a letter of admission to the Pope’s library only days before my scheduled arrival in Rome. Although my letters were in English, the responses were all in Italian. Fortunately, my knowledge of Spanish got me through the process and helped to rapidly increase my knowledge of Italian in preparation for my visit to Rome.

There was no exact date on the letter indicating an appointment. Just a letter of “Ammissione” and directions to the Cortile del Belvedere, which contained the Vatican’s secret archives. Equipped with a map and my precious letter of admission, I headed for the Vatican on my first morning in Rome along with my friend Jan, a fellow Tudor enthusiast, who intended to photo-journal our way through the Vatican. The sun was fiercely hot as we stepped into St. Peter’s Square through Bernini’s colonnade for the first time and took in the view of the Basilica which seemed both imposing and sur-real in spite of having seen it so many times on TV and on photographs.

There were no signs to direct us to the library, so we stopped in the book store to ask for directions to Bibliotheca Vaticani. The clerk directed us in Italian to the opposite side of St Peter’s Square, and, as we left, quipped sarcastically: “As if, you will get in…”

My letter instructed us to pass through the Via di Porta Angelica, The Angel Gate, an ancient archway that would lead us to Porta di S. Anna. We would recognize Porta di S. Anna because it was controlled by the Swiss Guard that has protected the Vatican for over five hundred years. At the tall wrought iron gate we caught our first glimpse of the young, blond, blue clad guards. Jan and I both presented identification and the letter of admission to the Vatican Library. We were received with some skepticism and discussion between the guards. Why wasn’t there a date of entry on the letter, why was it a photocopy, why were they not informed? So many questions!

I couldn’t give them a satisfactory answer to any of their questions, but all the same, I again pulled out my photo ID and reminded the young guard of the signature on the letter, copy or not, and urged him to let us pass. We were standing outside in the sweltering heat, and I was growing impatient with the delay, but grew even more so when the guard said, “You may pass to the next check point, but, Madam, cover your shoulders.” I was already modestly dressed anticipating entry to the Vatican, but I pulled a pashmina from my purse and draped myself in it, as I tried to forget the heat and focus on getting to the Pope’s library. As he let us pass, I asked him why the Swiss Guard was in Italy to guard the Vatican? He replied without hesitation. “Because we are the best.”

At the next check point up the hill from Porta di S. Anna, a guard scrutinized my letter and ushered us into an air-conditioned building were two men sat at a counter behind a glass barrier. Not quite certain why we were there, we pulled out our IDs and slipped the letter through a slot to one of the clerks.

The clerk turned to his colleague and the two discussed the letter, occasionally glancing up at us, before one finally turned to me and said, “You must sit here, while the other lady passes through to the library. Your ID is not acceptable.” I was painfully aware of our proximity to the letters and at that point being detained was not an option.

“Sir,” I said. “It is my name that is on that letter. If anyone is passing through, it is me. My identification is acceptable to The United States of America and the Swiss Guard, surely it is acceptable for entry to the Vatican Library considering the letter that I have presented.”

He looked at me with a mixture of resignation and astonishment, as I breathlessly waited to see what he would do next. The two men shared rapid words in Italian, our documents were returned to us, and along with them, two passes to the pharmacy. “You may leave.” is all he said. Jan looked at the passes and started to say “Pharmacy? We’re not going to….,” as I took her by the arm and headed for the door. We never did see the pharmacy or even find out where it was, but headed further into the depths of the Vatican to the Cortile del Belvedere. I knew we were only a stone’s throw from the Vatican Secret Archives.

The guard there greeted us kindly. After we described our journey from Porta di S. Anna, he immediately ushered us to the stately door at the far end of Cortile del Belvedere which was the entry to the library. We entered into a marble foyer where we were then guided by a porter into a hallway in front of La Officina de Segretaria where we were told to wait until someone would receive us.

In utter silence, we sat on black, strait-backed leather chairs in front of a marble wall plaque listing events relating to the library from the mid 1400’s to 2010. We were both aware that there was barely a sound in the building. We waited there in silence for 20 minutes before we again enquired about the “someone” who would receive us.

After a few more minutes the heavy doors of the Officina de Segretaria opened and a pleasant man greeted us in English and asked us to enter. After scrutinizing our documents and questioning me about my background, my reasons for wanting to see the originals and verifying my address, he asked me to fill out another form and sit for a photo. Shortly thereafter he handed me a Vatican Library photo ID with my photo and name on it, and with two hands he stood before me with a thick file of papers which he put into my hands and said, “These are the rules. Read them. Come back tomorrow, alone, and you may see the letters.” My heart sank, but I wasn’t going to argue. We thanked him and left. That evening I read the rules carefully. Among them, no photo equipment, no pens, no sharp objects, no cell phones, no food, and so on.

The following day I returned to the Vatican, alone, shoulders covered, with newly purchased not too sharp pencils from the Vatican store, a notepad, and my Vatican ID. When I entered the Porto di S. Anna I caught the eye of a Swiss guard surrounded by a group of students. I lifted my card and to my amazement, he ushered the students away to allow me to proceed and said “Pasa, Madame,” as he actually smiled to me. When I approached the second guard, I presented my card, to which he responded by saluting me and stepping aside so I could continue towards Cortile del Belvedere without revisiting the two clerks who had issued the “pharmacy passes” the previous day.

Upon entering the Vatican library this time my card was scanned by the porter in the foyer and the man from the day before reappeared. He greeted me cheerfully and promptly escorted me to a locker room where he told me to place my card against a small scanner on the left wall of the locker room. The number 42 appeared as I heard a click behind me of locker #42 opening. I placed my purse and phone in the locker, but kept my pencils, my notepad, my glasses and my ID and took a moment to say good bye to my helpful friend and thank him before he directed me on to the document reading room.

I headed down a corridor extending from the entry hall, flanked by two large curved staircases descending from a second-floor landing. Midway through the hallway there was a glass barrier with the same electronic scanner device attached to the side of it as the one mounted in the locker room. I swiped my card and the glass barrier rose up and slipped back in one sudden movement to open the way for me. As I passed through it snapped shut right behind me.

Ahead of me was the elevator that required another electronic ID swipe before it would open. Once I stepped out of the elevator, I took a wrong turn and walked into what looked like an ornate library of yesteryear. Old printed books lined the shelves of every wall, people read at tables, or were seated in leather chairs, but all was hushed and no-one looked up as I entered.

I found a librarian who quietly directed me to the Document Reading Room, and I proceeded through several rooms in complete awe of my surroundings until I found the Reading Room. There, I was graciously greeted by a very distinguished gentleman whom turned out to be Dr, Vian, my Vatican contact person. He spoke to me in Italian. I answered in English. We understood one another quite perfectly.

The Manuscript Reading Room was a large bright rectangular room with natural light streaming in through three large windows on the left wall. The ceiling was vaulted with an ornate medallion painted at its highest point. White and cream-colored marble flooring matched the cream-colored walls, white ceiling and the statutes in niches along the right wall. A deep red tile lining the periphery of the floor mirrored the color of the medallion above. Dr Vian worked from a dark wooden desk near the entry. Along the far end there was a five-panel dark wooden counter with two large wooden cabinets behind it and an open doorway to the far right. Above the cabinets was another statue, a cross, a large inscription and a thoroughly modern electronic clock that displayed the passing time in bright blue letters. The room held approximately 20 reading tables divided into two rows, each equipped with wooden book stands and a pair of wood dowels.

Dr Vian introduced me to three male librarians behind the long counter in the front of the room. They were all dressed in the same blue shirts and ties, but neither had name tags. One of them asked me to pick a seat and register by signing my name and seat number in a paper journal on the counter. He then opened a computer screen facing me and asked me to fill in a questionnaire, provide document numbers and my reason for wanting to see them. Dr Vian stepped in with the document numbers, and I found myself again explaining why I wanted to see the originals. The eleventh hour found me compliant. I wasn’t going to make a ripple of a wave now so I wrote as I was instructed to do. When I finished the librarian looked at the screen and noted a colored indicator that had popped up on the screen. “That is a special document!” he said, and looked oddly surprised. “I know,”I told him. The others gathered around and looked at me, then the screen, and me again. “It will be thirty minutes.” one of the three said. Again, no argument from me, but I did ask what I could do in the meantime, anticipating perhaps a coffee shop, a little browsing through the library or a garden to walk through. The reply was “You sit.” He pointed to my seat and I sat. I sat for a long time. Thirty minutes came and went as I memorized the statues, the medallion, the light fixtures, the security cameras, the floor tiles and the profile of the young Catholic priest studying ancient looking sheets of music at the desk beside me. I cringed as I watched him touch the pages and wondered if this would draw the attention of the librarians, the security cameras or Dr. Vian.

After 55 minutes, according to the digital clock in front of me, one of the three librarians came through the door opening along the right side of the room with a cart full of old looking books. The top book was a thin book with a thick, light blue paper cover. He picked it up as he gestured to me to come to the counter. I stepped forward, expecting an explanation for the delay, but instead he handed me the blue book.

I must have looked surprised, because he said. “It is what you came for.” I looked at the book, wrapped much like my elementary school books had been in my native Norway. I held it reverently with both hands, tenderly as I would a newborn, but still in utter shock as it started to sink in that someone had placed the letters Henry VIII had written to Anne Boleyn nearly five hundred years ago, into my hands. There was no white gloved person on the other side of the counter to unveil documents enveloped in protective fabric allowing me to gaze only from a safe distance. The letters were in my hands!

It is very possible that I forgot to breathe as I carried the book back to my seat. Recalling the rules, I kept the book visible and placed it on the wooden stand in front of me. Fully aware of the three librarians in front of me, Dr. Vian at the back of the room, and surveillance cameras pointed at me, I struggled to conceal my exuberance and tried keep my face in the same studious frame as the priest across from me. And probably failed completely. Of all the wonders I have seen through my travels, rarely has anything been so touching or so oddly exciting. I thanked God for my good fortune and dared to exhale as I opened the book. My hand touched Henry’s first letter as it was suddenly there before me, and I thought of Anne Boleyn.

So much has been said of her. She was brilliant, savvy, well-educated for a woman of her time, a champion for the reformation, a powerhouse in her own right, a woman whose elegance and charm were legendary, as much as her volatile temper and sharp tongue. However, when these letters were written Anne was a young woman in love with a man described as the most handsome man in Christendom, an Adonis, the most influential man in England and a force in international politics. To be this man’s darling would have been a heady and exhilarating prospect for any woman of her rank, but there is much evidence that Anne truly loved Henry, the man, as much as she adored her King. At the time of the letters, he was not yet the tyrant he would later become. One can only imagine the utter excitement the letters must have brought her when they were delivered to her at Hever Castle. I envision her there, young, alive and joyful, not the frightened and tormented Queen she was to become in her later days.

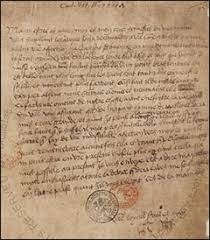

I was sad to see that each letter was glued into the book, efficiently numbered and stamped with the Vatican seal, in either red or black. From the reproductions I’d seen, I knew it would be difficult to read the script since Henry’s handwriting was so tortuous, and I wondered if Anne Boleyn had fared any better at deciphering their content. Thankfully, I knew what they contained and recognized the entries. One of the letters appeared to be written in a flurry, its strokes deeper, darker, and the page fraught with ink stains. Was he angered? Was he drunk? I don’t know, but this one letter stood out from the ones that appeared more thoughtful and composed. Henry didn’t like to write, but yet most of the letters were quite beautiful in their composition. Since they were glued to the page I couldn’t see if there were entries on the opposite side, nor was there anything to indicate that they had been sealed. The color of each had faded to varying degrees with darkened edges, but over all, they were all in pristine condition, excluding the Vatican markings.

Following the final letter there were more pages that were handwritten translations of the letters in Italian or copies in a more readable English script, apparently written during different time periods. Each was glued, numbered and stamped in the same manner. Nothing indicated by whom or when the letters had been stolen and brought to the Vatican.

I don’t know how long I lingered over these documents. But eventually I reluctantly closed the book after spending a long time with each letter and cherishing the moment. I gestured to one of the librarians that I would be leaving and he met me at the counter where I deposited the treasured book into his hands. He winked at me, tucked it under his arm like the morning newspaper and slipped through the passage at the far end of the room and disappeared back into the archives.

I watched in astonishment and with some sadness as the letters were so irreverently taken away to be tucked back into a Vatican vault, hidden away yet again. Although humbled by the privilege of having had the letters with me for a short time, my thoughts drifted to the question of who the letters rightfully belong to, having been written by an English King and so obviously stolen.

I decided to let that thought pass and exited back out through the many electronic check points of the Vatican. I wandered through the Porta di S. Anna with its young, blond Swiss Guards and finally reached the Angel Gates where I joined a group of tourists headed for St Peter’s Basilicas. Surely, even that could not possibly be more wondrous than having held Henry VIII’s love letters to Anne Boleyn in my very own hands.